While interning at LACMA in 2017, I came across a curious collection of 16th c. illustrations during an inventory project for special collections resources related to Costume & Textiles. This grouping of illustrations immediately struck me— one because of their small pocketbook-like size, and because of their depicted content:

preserved together in an archival box, the illustrations portrayed people and various scenes across the (mostly) upper echelons of society in Europe during the later half of the 16th century. Ascribed to each hand-colored illustration was a description for the viewer to contextualize the images:

Venetian Courtesan, from Album Amicorum of a German Soldier, Italy, 1595. LACMA (M.91.71.1-.101)

Album/alba amicorum (also known modernly as Stammbuch), grew to popularity in German universities of the 16th century as an autograph book and friendship album between students and scholars. This is the origin of our modern yearbook tradition in primary school education in the United States, as German immigrants imported this custom in the 18th century. [1]

Moving outside of the sphere of universities in the early modern period, the album amicorum served a purpose that was not unlike our modern social media as a means of recording, and in a sense— a way of maintaining a recorded social network across Europe to gain favor and display social capital. Just like a Facebook timeline, these books took on a collaborative nature in terms of text. As Raashi Rastogi states in his essay Early Modern Alba Amicorum and Collaborative Memory: [2]

“[…] June Schlueter, the definitive authority on early modern alba amicorum, explains, the album was traditionally passed around among students and teachers at university; it would “accompany its owner on his travels or was sent by messenger to a friend, an acquaintance, a nobleman, or a king with an invitation to sign.” Each contributor would reproduce a commonplaced quotation, offering the album owner advice or a meditation on friendship, together with a short dedication, the contributor’s signature, and the date and/or location of the autograph. In his treatise on alba amicorum, Philip Melanchthon describes the friendship album as a memory-aid, designed to “remind the owners of people.”

Beyond these textual relationships and recorded sentiments, album amicorum also served as a visual travelogue for the wandering scholar, soldier, and aristocrat to preserve memories of foreign places. For us, this can help serve as a looking glass into the past when it comes to a visual aid for the purposes of historic costume. However, this is not without its flaws: album amicorum of the period often contained professionally illustrated and pre-printed “stock” characters that one would expect to see on their travels— such as the Venetian courtesan, papal figures, and nobles in various continental dress. [3] The 16th century saw the emergence and popularity of the costume book, and it was no coincidence that these two genres became interrelated and vastly popular; as Western Europe at the end of the century became invested in printed works that created visual taxonomies of people, social strata, geographical areas, and professions to neatly arrange social knowledge in a rapidly expanding world. [4]

It is hard to delineate truth versus constructed perception in these visual travel narratives, and in a way they all serve as a curious curation of the reality of the book owner. This is not dissimilar to the way in which many social media “influencers” of our current world carefully craft a visual narrative about their lives to gain social capital; posing with cars they sometimes don’t own, being seen with people they are barely acquainted with, and posting photos of places they have never been. It is likely that many album amicorum creators participated in a construction of a similar idealized account.

As an example, note the similarities of the Gentlewoman of Venice depicted in the Album Amicorum of a German Soldier with the salacious interactive engraving of a Venetian Courtesan by Ferrando Bertelli in 1563:

(Images courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Album Amicorum of a German Soldier was produced in approximately 1595, while this widely-circulated engraving by Bertelli was made in 1563 (note the same Chopine posture, overall silhouette, fan, hairstyle, and kerchief.) I suspect that this image created by the German Soldier was likely a copy of Bertelli’s work, with some liberties taken for originality’s sake.

These images of costumes (both national and international) became widely available by the mid-to-late 16th century, and would have been an easy resource for traveling scholars and courtiers to fill up the pages of their album amicorum. These images often contained exoticized stereotypes of other nations, and served as an early form of a highly problematized ethnographic survey. [5]

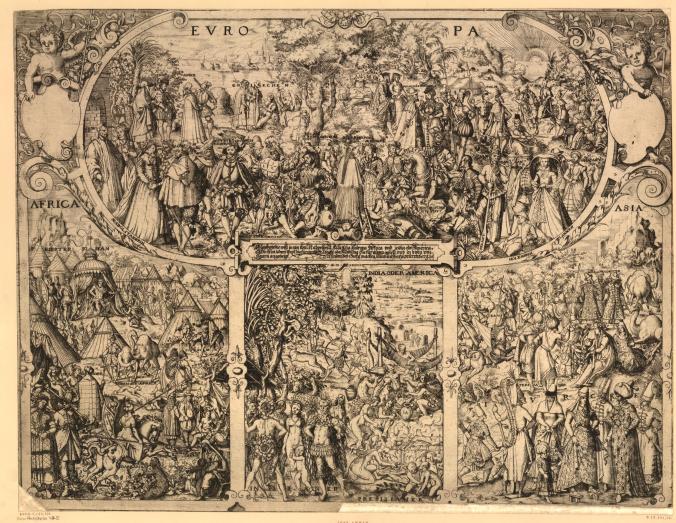

(Note even the visual hierarchy in Jost Amman’s Costumes of the Visual Nations of the World and how Europe is framed above the other continents (which include scenes of cannibalism)):

Image from Jost Amman’s Costumes of the Nations of the World, 1577. Image Courtesy of the British Museum. For a full and detailed view, follow this link: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1854-1113-173

‘Mauritana in Domestico’ From Trachtenbuch von Nurnberg (Costume Book of Nurnberg), co. CLXIII. Jost Amman (Switzerland, Zurich, active Germany 1539-1591) Germany, 1577. LACMA (Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Marvin M. Chesebro (M.87.164.3)

This image from Jost Amman’s Trachtenbuch is another example of the classification of people through printed works that came about in the late 16th century. This book contains images of people from around their known world, but with a heavy emphasis on individuals living across Europe. These costume books are heavily flawed in terms of their depiction of non-european cultures through a eurocentric and orientalized lens, so it is always best to view these sources with a heavy amount of skepticism in mind.

Keep in mind that for nearly 100 years before Amman’s Costumes of the Nations of the World Africans were being captured and enslaved by Portugal on account of their “Moorishness”, which was soon followed the enslavement of other ethnic groups. The first enslaved African Peoples were forcibly brought to the newly established colonies in North America by the English in 1619, but the slave trade was alive and well in England beginning in the 1560’s when Sir John Hawkins began his capturing of slaves with the support of elite English merchants.[6] These proto-ethnographic illustrations to classify the “other” served as a visual reminder to reinforce burgeoning ideas of white supremacy that manifested into the classifications of peoples, and the destructive scientific racism of the 17th through 20th centuries.

I am digressing here from the original topic and into the realm of the costume book, but I think it needed to be said that every source should be approached with these points of caution: what purpose does this image serve? who was the intended audience for this image? and who was the “authority” behind the image? These questions should continuously be asked when evaluating primary sources.

That being said, let us return to album amicorum.

Some of my favorite viewable album amicorum online offer up a wealth of delights:

Album Amicorum of a German Soldier, LACMA.

Since it has been the focus of this blog article, I recommend viewing the complete Album Amicorum of a German Soldier, which is available online through this link.

Album Amicorum of Jean le Clercq. 1576 – 1589

This Album, available for full viewing on HathiTrust is a beautiful example of an Album Amicorum being illustrated within an earlier printed work. There are many full-color illustrations throughout, including that of some delicious heraldry. (As an aside, I am very much not a fan of French styles of this period. The super-high plucked hairline, and wasp-waisted look is a bit much.)

Venetian Courtesan peering out from behind a veil. Album Amicorum of Paul Van Dale, 1576. The Bodleian Library, Oxford University. MS. Douce d. 11

This album made by Paul Van Dale is available online through the Bodleian Library at Oxford university, and includes beautiful illustrations of people across (mainly) Italy.

Album Amicorum of Jacob Heyblocq, 1645 – 1678. National Library of the Netherlands

This album is later than the period I am focusing on in this blog post, but it is a perfect example of an album amicorum: it contains hundreds of signatures and quotes from students and scholars of the period, with many in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. It also contains beautiful pencil and ink illustrations of Jacob’s travels as well, and I am a complete sucker for 17th century landscape studies— there’s just something so distant and moody about them.

[1] https://www.kettererkunst.com/dict/album-amicorum-stammbuch-memory-book-or-friendship-book.php

[2] RASTOGI, RAASHI. “Early Modern Alba Amicorum and Collaborative Memory.” Shakespeare Studies (0582-9399) 45 (January 2017): 151–58.

[3] Keller, Vera. “Forms of Internationality: The Album Amicorum and the Popularity of John Owen.” In Forms of Association : Making Publics in Early Modern Europe, edited by Paul Yachnin and Marlene Eberhart, 220–34. University of Massachusetts, 2015.

[4] Ibid, 224.

[5] Carvalho, Larissa. “Contact, Perception and Representation of the “American Other” in Sixteenth-Century Costume Books.” in The Myth of the Enemy: Alterity, Identity, and Their Representations, edited by Irene Graziani and Maria Vittoria Spissu, 235 – 244. Edizione Minerva, 2019.

[6] Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade : The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870. Simon & Schuster, 1997.