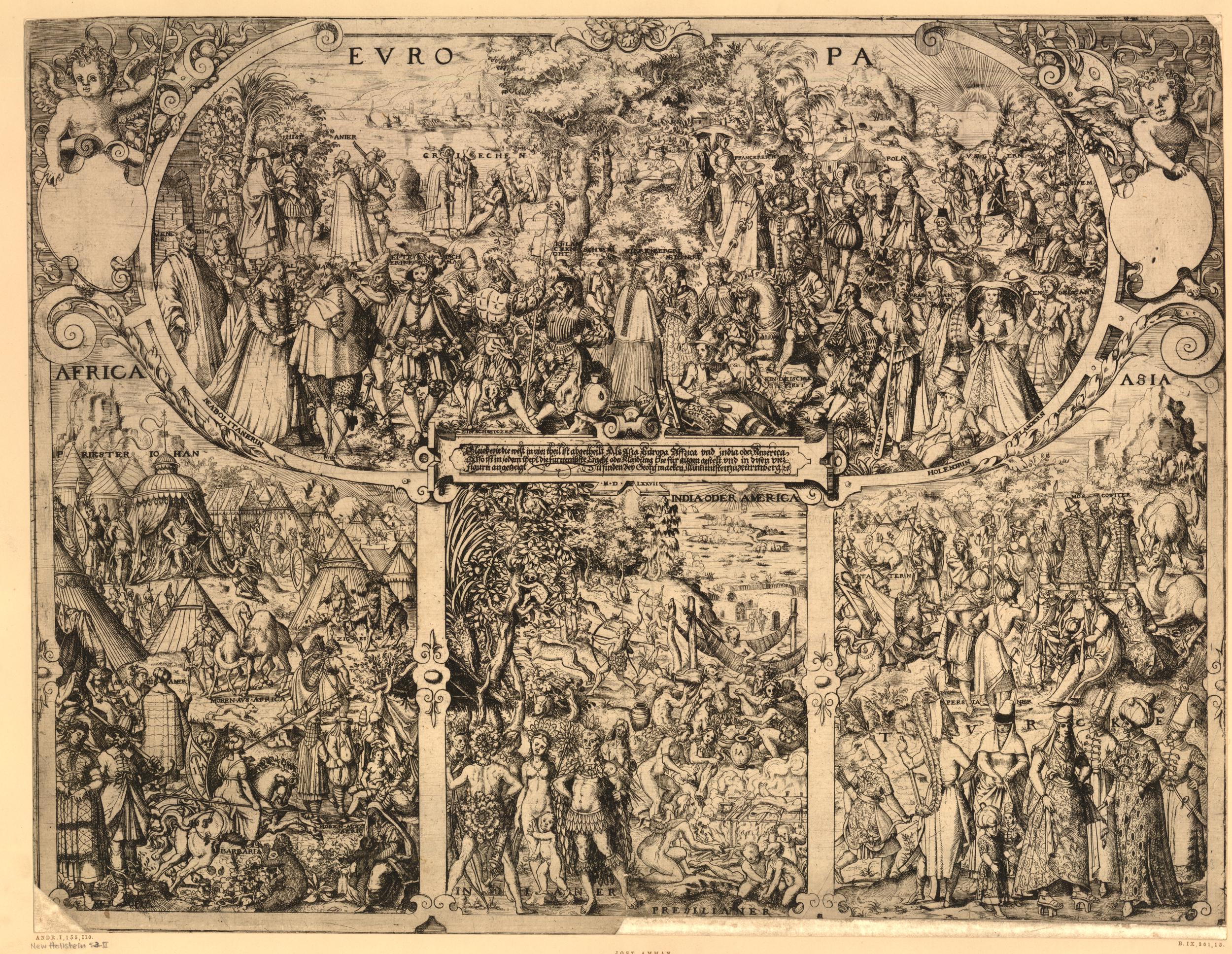

Analyzing the clothing of the courtesan in 16th century Italy presents us with a myriad of complexities regarding representation in the contemporaneous visual culture of the period. In this post, I hope to unravel some of these intricacies regarding the dress of women who were in equal measure both mythologized and maligned in both visual art and print culture of the period.

It is my hope that this post will serve as a basic starting point for those interested in investigating and representing the courtesan in historical costume studies.

Who were the ‘Cortegiana Onesta?

The courtesan— often noted in contemporaneous sources as the Cortegiana Onesta (the honest courtesan) were a social class of highly-educated courtesans in 16th century Italy that was separate from the general meretrice— the sex workers of the lower-class.

The Cortegiana Onesta represented a threat to the male-dominated social order of 16th century Italy, as these women were encouraged to pursue literacy and education, and had a degree of independence afforded to them that ‘respectable’ women of Venice did not have in terms of social and physical mobility between the public and private social spheres throughout the city.

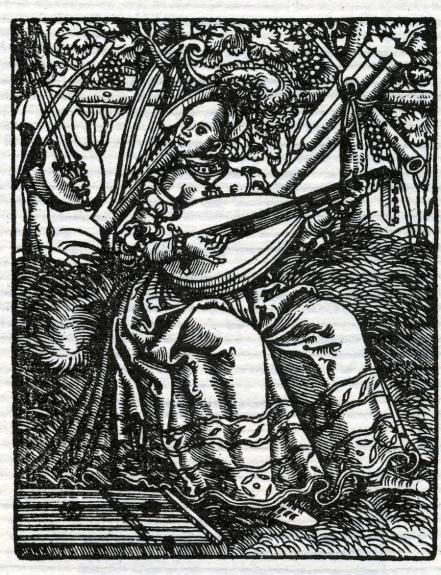

To be fashioned as a woman of cultural achievement, courtesans had to be well-read, capable of producing music, poetry, and dance— and without these skills befitting of a veritable classical muse, the courtesans would be no different than that of the meretrice, and thus insufficient of ensorcelling the attentions of men of the elite at length. The siren-song and musical capabilities of the courtesan was felt deeply in 16th century italy— The poet Antonfrancesco Grazzini (Il Lasca) even remarked on the Florentine courtesan Nannina Zinzera as such:

“Not even in heaven, among the happy souls,

is such sweet harmony to be found

Able to move mountains and still winds”

Veronica Franco and Gaspara Stampa were the two most famous courtesans of 16th century Italy. Both accomplished and published poets, they were notably compared to the mythological figure of the siren by their contemporaries; beautiful and dangerous— capable of luring men to ruin with their song. Their position in society was a precarious one; moving in and out male-dominated literary circles, Franco and Stampa had to constantly renegotiate the boundary lines of their gender and position within these spaces. Regardless of one’s actual profession, It was not uncommon for non-courtesan female authors in this place and time to be dismissed and disparaged by their male contemporaries as prostitutes due to the gendered lines being transgressed by crossing the boundaries of the private domestic sphere into the male literary sphere.[1] Courtesans had the mobility to move within these clearly delineated worlds, and were a constant threat to the social order. Still, despite attempts to regulate their practices and behavior, the polity of Rome and Venice merely tolerated their presence as a necessary evil that had the added benefit of courtesans existing as interlocuters between political figures who shared beds and divulged information.[2]

To understand their elevated position in society, it is helpful to look at what could be afforded to them in terms of the exchange of material goods and the domestic setting in which they lived and operated in. While this source is from a writer of the period describing a courtesan from Rome (as opposed to Venice) in the first quarter of the 16th century, it affords an interesting glimpse into the material lives of the Cortegiana Onesta:

“She lived in a most honourably appointed house, with many servants, men and women who continually waited on her. The house was equipped and provided with everything, so that any stranger who entered and saw the furnishing and ranks of servants thought a princess lived there. Among other things, there was a reception room and a chamber and a smaller chamber so grandly decorated that there was nothing to be seen but brocades, and the finest carpets on the floor.

Matteo Bandello Novelle III, v2 pp 461-2

In the little bedroom where she withdrew when some great personage visited, there were hangings covering the walls, all of cloth-of-gold riccio sovra riccio, ornately and delightfully worked. Then there was a cornice, all picked out in gold and ultramarine, masterfully made: pm ot were exquisite vases made of a variety of precious materials […]”

This exhaustive source describes the household goods in the inventory list of Julia Lombardo in 1569— a courtesan of Venice:

“In the chamber facing S. Caterina:

Rogers, Mary, and Tinagli, Paola. Women in Italy, 1350-1650: ideals and realities: a sourcebook / selected, translated and introduced by Mary Rogers and Paola Tinagli. Manchester; New York: New York: Manchester University Press, 2005.

A painting of Our Lady in a walnut frame, with gilded columns.

Another large painting with Christ and various figures, with fittings of gilded stucco.

A painting with the head of St. John the Baptist.

A large lamp of gilded bronze

Five paintings with three different figures, imitating bronze.

A small painting on panel with a head sketched in.

A parrot’s cage, gilded all over, with a red cover

A walnut writing desk

A walnut bed, with columns for curtains gilded with several motifs, which the maids say comes from Madama Cecilia Colonna…

Two small lady’s chairs of old gilded leather

A green harpsichord

Pieces of spalliere panelling for the said chamber, with fragments of figures

Gilded leather to furnish the said room

Carpeting for the chests …

…and several chests containing chemises, scarves, and other clothing, bed-coverings and household linens, carpets, and furnishing fabrics, silversmith’s work and coins. The adjoining studiolo included:

A bronze figure with a bow in hand

A casket banded with steel, covered with black velvet, with a tin box with trinkets inside…

A bag with pearls… a bag containing a little gold crucifix, with four rubies, not very valuable, with five pearls

A gold needlecase

A small gold container, formed like a small dolphin…

A crown of blue enamel, with olive motifs and gold motifs

A crown of cornelian

An ebony crown, small with motifs gilded in Perugia work.

On the shelves of the said studiolo:

Vases and flasks of various kinds of reticella glass, 50 pieces.

Three porcelain dishes, two smaller dishes

Five porcelain bowls

A painting of Piera

A painting of Dante

Books, old

Three large Majolca dishes” [3]

The luscious descriptions of these interior spaces makes it easy to imagine the set in which the courtesans existed as actresses entertaining their guests by leading them through a sensory paradise of visual and tactile pleasure. Lombardo’s wealth was not limited to this cross section of her inventory— she had owned a rustic retreat that paid rents in produce grown on the estate from the 158 campi (fields). [4]

These were not the ramshackle surroundings that existed for the meretrice who conducted business in the dark of the alley— these were the near palatial abodes of those who were entertaining noble guests.

So, what did the courtesans wear?

The courtesans of Venice wore clothing that was indistinguishable from those of the other Noblewomen, despite failed sumptuary measures enacted by the religious elite to distinguish them from the “respectable” women of Venice.

Cesare Vecellio comments in his famous work:

“Courtesans who wish to get ahead in the world by feigning respectability go around dressed as widows or married women. Most courtesans dress as young virgins anyway. In fact, they button themselves up even more than virgins do. But a compromise must eventually be reached between the wearing of a mantle that hides their bodies and their need to be seen, at least to some extent. Finally, courtesans are forced to open up at the neck, and one recognizes at once who they are, for the lack of pearls speaks loud and clear. Courtesans are prohibited from wearing pearls. Indeed, in order to remedy this situation, some arrange to be accompanied by a lover-protector, borrowing his name as if the two of them were married. In this way courtesans feel free to wear things forbidden to them by law.

Habiti Antichi e moderni di tutto il mondo (1590)

Aside from this limitation, however, they dress in the most lavish manner, their underwear including embroidered hosiery, petticoats, and undershirts, and garments of silk brocade. Inside their high clogs they wear Roman-style shoes. I am speaking, of course, of the high-class courtesans. Those, on the other hand who exercise their wicked profession in public places wear waistcoats of silk with gold braid or embroidery and skirts covered with overskirts or silk aprons. Light scarves on their heads, they go around the city flirting, their gestures and speech easily giving away their identity.”

Given, the various sumptuary measures put forth by the Venetian Magistrates (The Provedadori) were not limited to just the courtesans, but also of the women and men of the noble patrician houses in Venice. With growing concerns to the radical shift in sartorial display at the beginning of the 16th Century in Venice, legislation soon followed by the authorities. In 1512, the Venetian Magistrato alle Pompe (The high commission on Luxury) was founded, and began to enact legislation against the wearing of cloth of gold and silver, rare types of silk, and cut sleeves with decorative trimmings.

In 1562, a sumptuary law was enacted against the Courtesans of Venice, forbidding them from the wearing of silk, jewelry, and limited them to the wearing of cloth made of 50% wool— in addition to the regulation of luxury and display inside of their residences.[5] We know from the visual and textual evidence that this rule was flouted by the women of the Cortegiana Onesta, as Vecellio’s aforementioned account— in addition to the description of Julia Lombardo’s inventory— takes place after these sumptuary measures were put in place, and speaks of how they manage to get around these rules regarding dress in addition to how little the courtesans took these rules seriously.

The Clothing

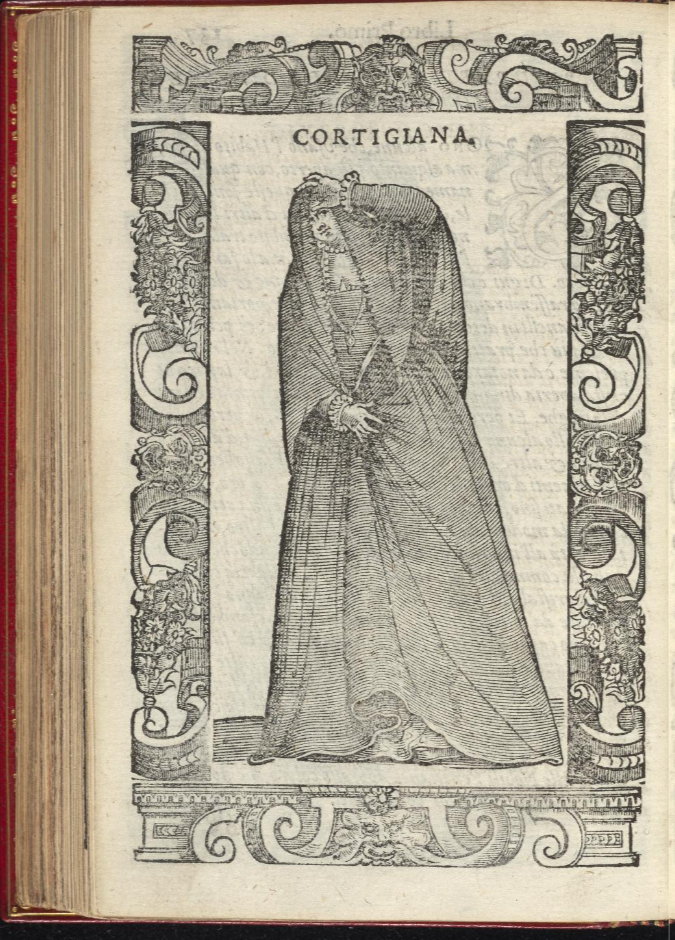

In this manuscript illustration from Mores Italiae, a young woman— presumably a courtesan peers out from beneath her veil in the guise of a married woman or widow. Vecellio noted that unmarried young Venetian women would wear a fazzuolo of white silk when leaving the house, taking extra care to cover the whole of their face and bosom, and in the case of the print above, a married or widowed woman would don a cappa— a veil of black. In Florence, courtesans were mandated to wear a veil of yellow silk as a badge of their office after a sumptuary measure was enacted in 1546, though these laws naturally did not apply to Venice. Thus, in the print culture of the period, we rely on the cue of “looking”— that is of the woman lifting the veil to peer out at the viewer as a visual cue to her profession as one of the Cortegiana Onesta.

The woman wears what appears to be a sobering black silk sottana or veste ( petticoat dress, or overgown) in a style similar to the Florentine dresses of the period— a high-waisted closed-front imbusto (bodice), with a scandalously low décolleté front. It’s interesting to note that the courtesans of Venice did not always exclusively wear the ladder-laced style they are known for, but instead unsurprisingly adopted fashionable styles more broadly from across Italy. The Sottana would have been heavily stiffened at this point with a series of stiffening layers (the doppia) comprised of stiffened linen paste buckram, bombast, wool, and/or pasteboard/cardboard.

By the 1520’s and well into the 1540’s in Italy we see this shift towards the modification of the women’s silhouette to favor a flat-fronted look of the stiffened styles that would dominate fashion for the next several hundred years through the eventual adoption of stays and corsetry in the subsequent 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. The painting above by Paris Bordone shows this change from the soft curved bodice silhouettes of the first quarter of the 16th century, into which by now favored the uniformly barreled silhouette. The visual evidence is supported by the (limited) extant examples of dresses from the period— namely, the funeral dress of Eleanora di Toledo, which the bodice was interlined with a stiffened linen interior, and a separate bodice made of velvet was worn beneath the overgown.[6] The differences in terminology between the sottana and the veste are vague when it comes to defining 16th century Italian fashion. Roberta Orsi Landini notes in Moda a Firenze that the Sottana is a petticoat usually always sewn with the inclusion of the bodice unless otherwise specified, and it came to replace the veste as an outer garment for 20 years between the 1540’s and 1560s, after which it remained an underdress for the outergown, or veste. [7]

Peeking out of the décolleté in the portrait above by Bordone in a rather haphazard way is the colletto. Landini defines the colletto as such: “Partlet. Decorative, independent garment, worn above the smock to veil low necklines and fastened at the waist with ribbons or cords.” These were often made with a either silk organza, net, linen, or lace. As Orsini notes, “The partlets were made up by the veil-makers, who not only wove veiling but also made the cloth up into garments” [8]. Another type of partlet was the gorgiere— a partlet with a collar and usually decorated with a ruff.

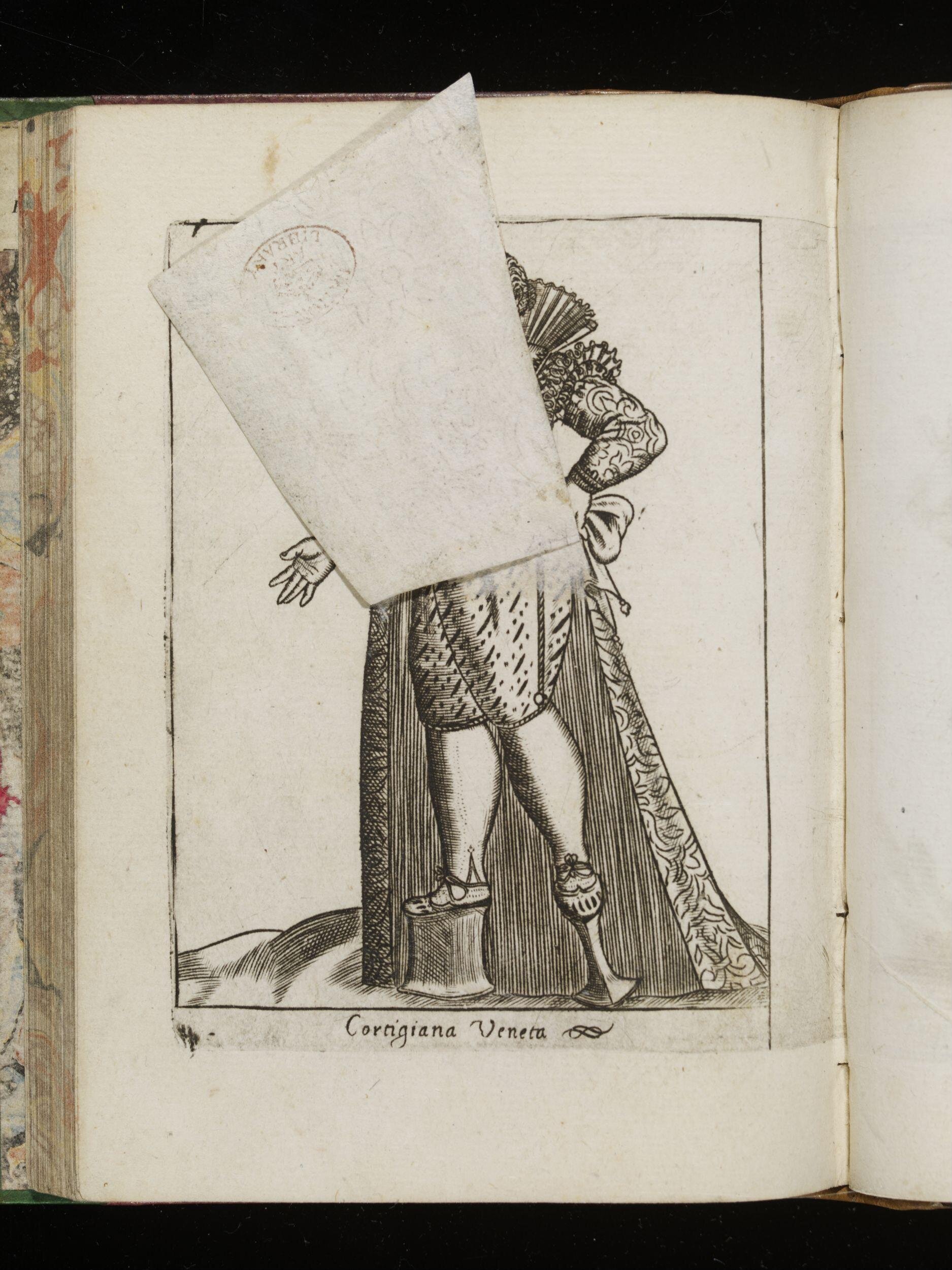

In this infamous engraving of the Venetian courtesan, we are afforded a view of the garments and accessories which often scandalized the elite of 16th century Italy. The flap of the engraving lifts open at her Falda (skirt) to reveal the courtesan wearing a pair of men’s breeches, or calzoni as they were known. As Lynne Lawner notes in The Lives of the Courtesans, “The ambiguity must have been appealing to the men of that time, who enjoyed mingling the natural and “unnatural” ways of making love, often keeping male lovers and alternating them with their chosen courtesans.”[9] It is interesting to note that in the wardrobe accounts of Eleanora di Toledo, there appears to be a pair of crimson calzoni listed among the items. Landini notes that due to their association with prostitutes, they were not common, but could have been useful for keeping warm and for riding horses.

(Above: and again, the view of the Courtesan by Pietro Bertelli in Diversarum Nationum Habitus, with the movable skirt flap affording a glimpse into the underclothing of the Cortegiana. I particularly enjoy the details in this rendition as you can see clearly how the Pianelle were fastened, with clear evidence of clocked stockings, in addition to the pinked and slashed fabric of the calzoni.)

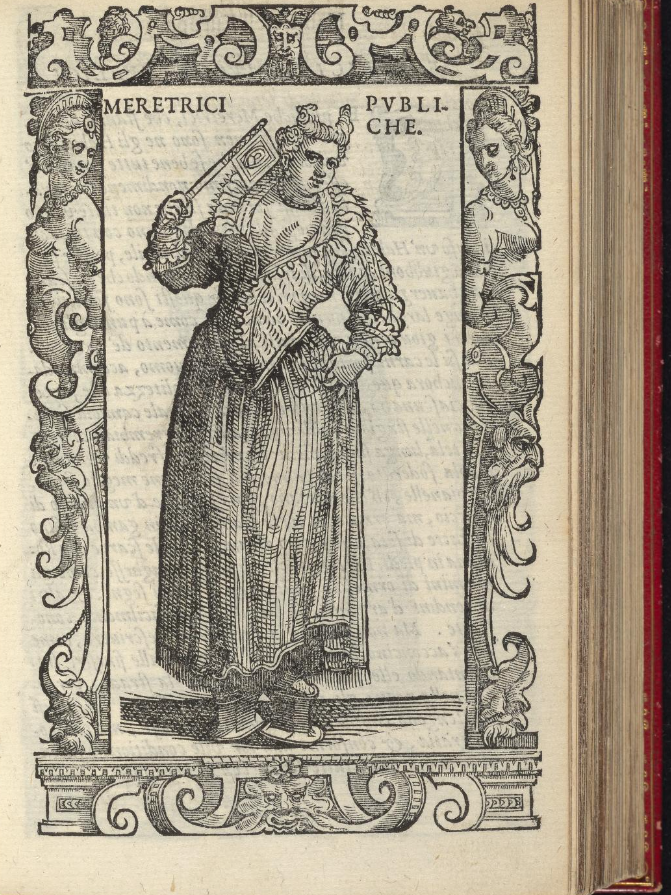

The image of the Meretrici Publiche or Prostitute in Public in Vecellio’s work. Note the scandalously transparent Falda (skirt), Spanish-style vest bodice, and the high pianelle.

Adorning the feet of the courtesan are the high pianelle, or chopines as we commonly know them today. A direct evolution of the medieval patten, and inspired by the ornately decorated Turkish bathhouse slippers, the wearing of the pianelle to achieve an unnatural stature was a common target of criticism among the magistrates of Venice; as these shoes were richly ornamented and often covered in cloth of gold or silver. While these shoes often required assistance from servants to keep the wearer upright, they also served the purpose of keeping the hems and trains of dresses from dragging through the mud. Lawner notes that beyond extravagant expense, the wearing of the pianelle also produced injuries and very real risks to pregnancies in women resulting from falling over in the city streets while wearing these shoes. As these were worn by not just courtesans but by patrician women, their danger to the wives of Venice resulted in intense scrutiny and condemnation among the magistrates.

https://www.europeana.eu/item/92065/BibliographicResource_1000056122788?q=bernardus%20paludanus

While it is unknown if the intent of the representation in the album amicorum illustration above is that of a courtesan, there are some interesting things here to note— this iteration was heavily inspired by the Vecellio woodcut in a similar vein of a woman bleaching her hair. In the 16th century, having lightened hair was synonymous with health, virtue, and therefore beauty. The dominant Neoplatonist philosophy at the time believed that beauty was a manifestation of the divine, and that when the humors were in alignment, blonde hair would be the expression of that unity.[9] Therefore, the bleaching of hair was a common cosmetic practice among the women of Venice. As Courtesans aspired to be veritable glimmering jewels within the ornamented boxes of both their abodes and covered gondolas as the human embodiment of desire, it can be assumed that the courtesans would have engaged in this practice.

Another interesting observation about this illustration is the camicia (shift). The voluminous almost “a dogale” sleeves would have no doubt angered the provedadori in the first half of the 16th century, though at the time that this time was more normalized into the expression of 16th century Italian women’s fashion.

These various iterations of dress remained the mode of fashion for the courtesan in Venice for a little over 100 years with very little change apart from hairstyles, bodice length, and the eventual introduction of other types of accessories such as the rebato at the end of the 16th c. as Venice became a powerhouse for lace production. While it is easy to glamorize the life of the cortegiana onesta from these sumptuous descriptions, we must also acknowledge that their path that was given to them was one of the very few that women could take with any sense of self-agency— and theirs was not an easy path by any means. Risk of disease, physical harm, or ruin by the state lurked around every turn like a monstrous serpent waiting to pull them by the ankles into the murky depths of the Venetian canals. Still, it is important to acknowledge the very real power that these women held as both art and fashion icons in their own right.

Author’s Notes:

Well, it’s been awhile since the last time I posted anything. I’m hoping to continue posting with some documentation for a recent gown I’ve made inspired by the Bordone painting featured above. If not that, I have a few other good things in the works for this site. I hope you enjoyed the little foray into the world of the cortegiana onesta.

Bibliography

[1] Quaintance, Courteney. Textual Masculinity and the Exchange of Women in Renaissance Venice. University of Toronto Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctv1005cx3.

[2] Lawner, Lynne. Lives of the courtesans: portraits of the Renaissance / Lynne Lawner. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

[3] Rogers, Mary, and Tinagli, Paola. Women in Italy, 1350-1650: ideals and realities: a sourcebook / selected, translated and introduced by Mary Rogers and Paola Tinagli. Manchester; New York: New York: Manchester University Press, 2005.

[4] Santore, Cathy. Julia Lombardo, ‘Somtuosa Meretrize’: A Portrait by Property. Renaissance quarterly 41, no. 1 (1988)

[4] Lawner, Lynne. Lives of the courtesans: portraits of the Renaissance / Lynne Lawner. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

[5] School of Historical Dress. 2023. Patterns of Fashion 3 : The Content Cut Construction and Context of European Men’s and Women’s Dress C. 1560-1620 New revised paperback ed. London: School of Historical Dress.

[6] Niccoli Bruna and Roberta Orsi Landini. 2019. Moda a Firenze 1540-1580 : Lo Stile Di Eleonora Di Toledo E La Sua Influenza = Eleonora Di Toledo’s Style and Influence. Firenze: Mauro Pagliai editore.

[7] ibid.

[8] Lawner, Lynne. Lives of the courtesans: portraits of the Renaissance / Lynne Lawner. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

[9] Stephens, Janet. “Becoming a Blond in Renaissance Italy.” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum, November 2, 2023. https://journal.thewalters.org/volume/74/note/becoming-a-blond-in-late-fifteenth-century-venice-a-new-look-at-w-748/#edn-7.

Other consulted sources:

Vecellio, Cesare, and Chrieger, Cristoforo. De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diuerse parti del mondo libri dve / fatti da Cesare Vecellio; & con discorsi da lui dichiarati. In Venetia: Presso Damian Zenaro, 1590. (digitized via the Getty Research Institute) https://archive.org/details/gri_33125012247702

Beinecke MS 457, Mores Italiae. (digitized via Yale University Digital Library) https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2003570